In cavalry

The passion for horses, which characterised Baracca throughout his life, manifested itself right from his childhood. A lover of outdoor living, already during his boarding school years, the young Francesco found an outlet and relief from the monotonous school routine by mounting a saddle and taking riding lessons, with the approval of his father Enrico, a great horse-lover, arousing his mother Paolina’s concern. The much longed-for summer holidays spent at the country villa in S. Potito, became the ideal opportunity to go for rides in the surrounding area and, above all, to try jumping over all sorts of obstacles, attracting an audience made up of the many farming families in the area who gathered on Sundays to watch.

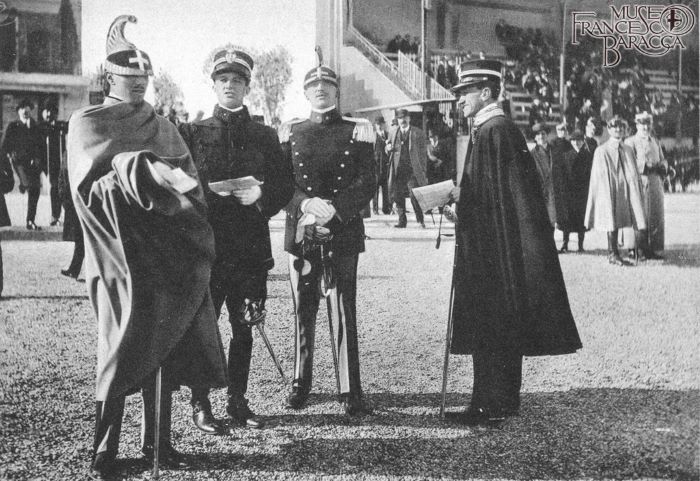

When Baracca chose to pursue a military career, his aspiration to become a student of the Cavalry course was almost taken for granted and in 1909, after two years of study at the Military School of Modena, he graduated with good marks and was awarded the rank of second lieutenant in the Cavalry. His excellent results in riding earned Francesco an assignment to the 2° Reggimento Piemonte Reale Cavalleria (2nd Piedmont Royal Cavalry Regiment), one of the oldest and most prestigious regiments of the Royal Army, and he was transferred to Pinerolo, at the Cavalry School to complete his studies. Here the days passed quickly for the new officers, divided between hours of theory and practice, riding the numerous horses available at the School, not counting the two steeds personally assigned to the second lieutenant, the “office” one and the “property” one.

Following a well-established tradition, a lira was paid into a common fund for every fall from horseback, a frequent occurrence for many riders, but not for Baracca, who also had to add a bottle of champagne, as it was his first tumble in two years. In Pinerolo, Baracca enjoyed more freedom than in his Modena years and began to frequent haunts of the Piedmontese high society of the time. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Cavalry was still considered the “noble” part of the army, both in military terms and for the mundane aspects intrinsic to the figure of the cavalryman, dashing in their uniforms amid glittering sabres and spurs.

These diversions, however, did not detract from the commitment and care that Baracca showed in his preparation and hard training, sometimes putting himself on an iron diet when the scales showed signs of burdening, and on completion of his studies at Pinerolo, he achieved top marks in equestrianism, along with only four colleagues out of 57.

Once arrived at the regiment’s 1st squadron in Rome, in late summer 1910, he was assigned the command of a platoon and, above all, the instruction of scouts and elite cavalrymen. During some excursions with his men in the countryside around Centocelle, Francesco witnessed several flights and immediately wrote about that to his mother, stating that “a general, some days ago, told us that cavalry officers, the intrepid and enterprising part of the army, will have to devote themselves to aviation, which will bring great changes in future wars”.

Despite a certain interest that leaked from the neutral tone of the letter towards the opening of an aviation course at the Centocelle airfield, Baracca told the apprehensive Paolina that he had no intention of enrolling himself and that he was very busy with his horses.

At that time, in fact, the complementary course at Tor di Quinto was also opening. In addition to his usual duties at the squadron, Francesco was intent on preparing for the International Horse Competition in Rome, where he achieved good placings in several categories and won the Hausmann watch that he wore until his death, and for the Horse Competition in Turin organised by the National Zootechnical Society in spring 1911.

Such was his dedication to training that he neglected the much-loved and glittering social life he led in Rome, including fox hunts, dinners in restaurants, opera performances at the theatre and café-concerts.

Of course, money was never enough and Enrico willingly granted the appropriate financial support for his son’s numerous and expensive activities, not forgetting clothing and riding accessories.

When he decided to devote himself to aviation, Francesco never neglected his passion for horse riding and took his beloved horses with him on every journey, even during the war years.

On the occasion of the retreat from Caporetto, Baracca and his comrades were forced to abandon the base of S. Caterina di Udine: Francesco, as commander of the 91a Squadriglia (91st Squadron), was the last to leave and was uncertain between flying off or joining the squadron of the Genova Cavalleria (Genova Cavalry), which was defending the base camp, and mounting his horse to charge the Austrians.

Further fundamental evidence of this love, remained anyway unchanged, was his decision to adopt as his personal symbol the prancing horse, in honour of his regiment and the army to which he has always belonged.

Grazie al ricco epistolario pervenutoci, è possibile ricostruire, almeno parzialmente, la dimensione privata di Francesco Baracca, contraddistinta da passioni ed interessi comuni ai giovani di buona famiglia all’inizio del Novecento.

Amante del teatro e della lirica fin dall’adolescenza trascorsa a Firenze; il giovane sottotenente lughese, dopo aver frequentato il duro biennio alla Scuola Militare di Modena, potè godere della vita mondana di Pinerolo, con frequenti puntate a Torino, insieme agli amici e colleghi della Scuola di Cavalleria.

Amante del teatro e della lirica fin dall’adolescenza trascorsa a Firenze; il giovane sottotenente lughese, dopo aver frequentato il duro biennio alla Scuola Militare di Modena, potè godere della vita mondana di Pinerolo, con frequenti puntate a Torino, insieme agli amici e colleghi della Scuola di Cavalleria.

Nel settembre del 1910, una volta giunto a Roma, assegnato al reggimento Piemonte Reale Cavalleria, Francesco mantenne la promessa fattasi di “darsi alla pazza gioia ”: acquistò così abbonamenti per le barcacce nei teatri Costanzi ed Argentina e per le cene in eleganti restaurants. Iniziò inoltre a frequentare numerosi cafè-concerto , fra i quali spiccava il Salone Margherita.

Alcune volte, accompagnato da amici e rigorosamente in borghese, si divertiva a “far un baccano d’inferno ” in qualche ristorante meno distinto.

La propensione a far baldoria gli costò pure un trasloco da Via Palestro, poiché la padrona di casa “si lagnava perché facevamo troppo chiasso ed allora perdetti la pazienza e me ne andai ”.

Desiderando che “le giornate fossero lunghe lunghe per poter vedere tutto ciò che desidero ”, Francesco non mancò di visitare monumenti ed esposizioni, ma soprattutto fu un assiduo partecipante delle cacce alla volpe nelle campagne romane, appuntamento immancabile per gli eleganti ed audaci ufficiali di cavalleria e per la nobiltà della Capitale.

La dolce vita romana era pure allietata da gite fuori porta , in automobile, con signore e signorine italiane e straniere. Nonostante le facilitazioni date dallo status di cavaliere, il tenore di vita di Baracca richiedeva un aiuto economico da parte della famiglia, con frequenti note di spesa riguardanti l’abbigliamento ed accessori “perché qua bisogna andare inappuntabili ”.

Risale probabilmente al periodo romano anche l’affiliazione alla Massoneria come appartenente al Rito Scozzese Antico ed Accettato col XVIII grado all’Obbedienza di Piazza del Gesù.

Francesco passò alcuni mesi a Rieti , in distaccamento con il proprio squadrone, verso la fine del 1911.

Il confronto con la sfavillante vita mondana capitolina risultò impietoso e Baracca si dovette accontentare di serate al cafè o al circolo, trovando uno sfogo molto parziale in lunghe passeggiate a cavallo nel tempo libero ed augurandosi di partire per la Libia, dove era scoppiato il conflitto con l’Impero Ottomano, “tanto per toglierci da questo paese poco simpatico ”.

Una volta rientrato a Roma, di nuovo immerso nel tourbillon di eventi, cominciò pure a schettinare nei giorni di brutto tempo. Temendo di incappare in un altro poco piacevole distaccamento nei mesi successivi, Francesco avrebbe voluto “dividersi in dieci ” per non mancare a tutti gli eventi mondani . Nel frattempo, all’inizio della primavera del 1912, aveva sporto domanda per prendere il brevetto di pilotaggio in Francia.

Per non far preoccupare l’apprensiva madre Paolina, Francesco trovò il pretesto dello studio delle lingue in quanto “qui a Roma sono indispensabili mentre ora non ho davvero il tempo di mettermi a studiare, ma in estate lo farò ed occorre che Papà mi prepari un viaggio all’estero ”.

Gli anni spensierati trascorsi nella Capitale stavano per concludersi ed il 25 aprile 1912 Baracca partì in treno alla volta di Reims, in Francia.

The Roman period

Thanks to the rich epistolary that has come to us, it is possible to reconstruct, at least partially, the private dimension of Francesco Baracca, marked by the passions and interests common to young people from good families in the early 20th century.

A lover of theatre and opera since his adolescence spent in Florence, the young second lieutenant from Lugo, after attending the tough two-year period at the Military School of Modena, could enjoy the social life of Pinerolo, with frequent trips to Turin, together with his friends and colleagues from the Cavalry School.

In September 1910, once arrived in Rome and assigned to the 2° Reggimento Piemonte Reale Cavalleria (2nd Piedmont Royal Cavalry Regiment), Francesco kept his own promise to “go wild”: he bought season tickets for the “barcacce” at the Costanzi and Argentina theatres, as well as for dinners in elegant restaurants. He also started to frequent numerous café-concerts, among which the Salone Margherita stood out.

Sometimes, accompanied by friends and strictly in plain clothes, he enjoyed “making a hell of a racket” in some less distinguished restaurant.

His propensity to revelry even cost him a move from Via Palestro, as the landlady “complained that we were making too much noise and so I lost my patience and left”.

Wishing that “the days were very long, in order to see everything I wanted to”, Francesco did not miss to visit monuments and exhibitions, but above all he was an assiduous participant in fox hunts in the Roman countryside, an unmissable appointment for the elegant and daring cavalry officers as well as for the nobility of the Capital.

The Roman dolce vita was also enlivened by trips out of town, by car, with Italian and foreign ladies and young ladies. Despite the facilities given by the military status, Baracca’s standard of living required financial help from the family, with frequent expense notes concerning clothing and accessories “because here you have to go impeccably”.

His affiliation to Freemasonry as a member of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite with the 18th degree to the Obedience of Piazza del Gesù probably dates back to the Roman period too.

Francesco spent a few months in Rieti, on detachment with his Squadron, towards the end of 1911.

The comparison with the glittering social life in the capital was pitiless and Baracca had to be happy with evenings at the café or the club, finding a very partial outlet in long horseback rides in his spare time and wishing to leave for Libya, where the conflict with the Ottoman Empire had broken out, “just to get away from this unpleasant country”.

Once back in Rome, again immersed in the tourbillon of events, he even began to rollerskating during bad weather days. Fearing another unpleasant detachment in the following months, Francesco would have liked to “split into ten” in order not to miss all the social events. Meanwhile, in early spring 1912, he had applied for his pilot licence in France.

In order not to worry his apprehensive mother Paolina, Francesco found the pretext of studying languages as “here in Rome they are indispensable, while now I really don’t have time to start studying, but in the summer I will, and Dad will have to prepare a trip abroad for me”.

The carefree years spent in the capital were coming to an end and on the 25th of April 1912 Baracca left by train for Reims, France.